Driving south from Jerusalem, the landscape is dominated by an artificial cone-shaped mountain on which Herod the Great built the fortress-palace he dedicated to himself. Herodium rises 758 metres above sea level with breathtaking views overlooking the Judean Desert as far as the Dead Sea and the mountains of Moab. It is one of the most important and unique building complexes built by Herod and is considered among the most impressive structures of the ancient world.

Coordinates: 31° 39′ 57″ N, 35° 14′ 29″ E

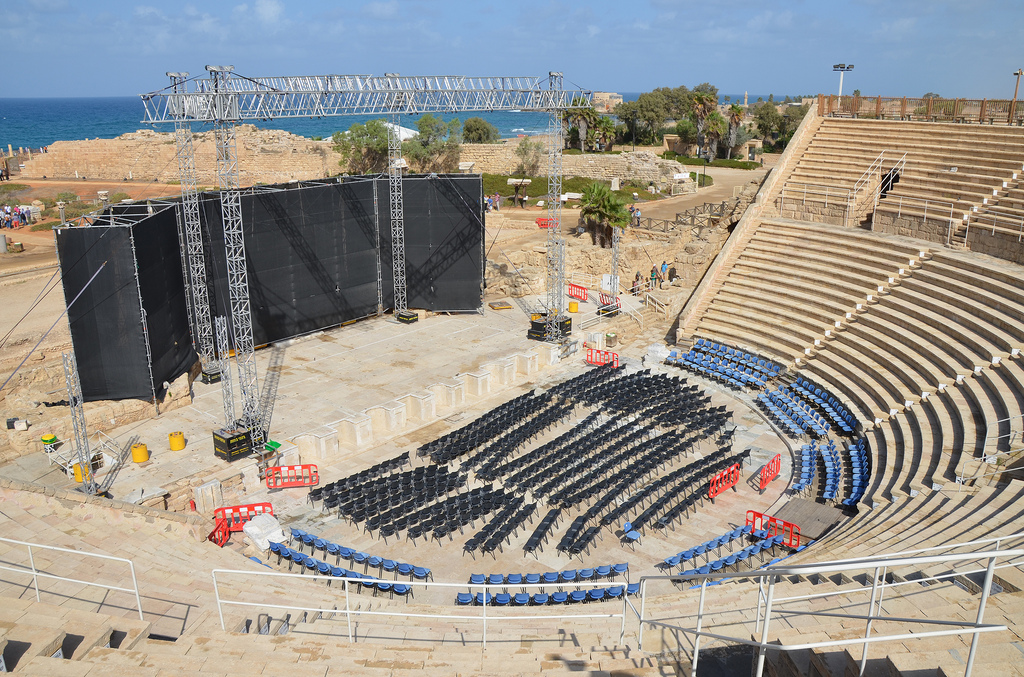

The construction of Herodium began around 25 BC on the location of his victory over his Hasmonean and Parthian enemies in 40 BC. To commemorate the event, the King built one of the largest monarchical complexes of the Roman Empire, which served as a residential palace, an administrative centre and a mausoleum. Herod built many magnificent palaces throughout the Land. These palaces included guest rooms, bathhouses, swimming pools, and luxurious gardens, all decorated in the style of the lavish palaces of Rome. It was at Herodium that Herod entertained Marcus Agrippa, the son-in-law of the emperor Augustus, in 15 BC.

Herod planned the site as a complex of palaces consisting of three parts:

- 1. The fortified mountain palace; The combination of fortress and palace is a uniquely Herodian innovation, which he repeated on several other sites, including Masada.

- 2. Lower Herodium, combining a magnificent recreation area, a bathhouse, an administrative centre, and a system of structures to serve during the King’s funeral (including the procession way).

- 3. The slope on the northern part of the hill where Herod built a vast three-story high mausoleum that could be seen from afar.

The search for Herod’s tomb was one of Israel’s most significant archaeological quests. The historian Josephus wrote that Herod was buried in Herodium, but archaeologists could not locate the tomb until 2007. Finally, after thirty years of searching at the site, the late Prof. Ehud Netzer of the university’s Institute of Archaeology announced that he had found the tomb of Herod. He discovered the remains of a large tomb and opulent coffins on the northern slope of the mountain facing Jerusalem.

Following Herod’s death, his son and heir, Herod Archelaus, continued to reside at Herodium. After Judea became a Roman province, the site served as a centre for Roman prefects. During the Great Jewish Revolt of AD 66, the Zealots captured the fortress but then handed it over without resistance to the Romans following the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70. Fifty years later, Herodium was captured again by the rebels during the Bar Kokhva Revolt. As part of their defence measures, they dug tunnels around the cisterns and hid there. During the Byzantine period, Lower Herodium was rebuilt on top of the ruins and constituted a large village with three churches. The settlement appears to have continued until the 9th century AD, after which the site was abandoned.

Today, Herodium is a national park under the management of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. An excellent archaeological site complete with a labyrinth of cool underground caves and tunnels, the Park recently opened a small Visitors Center with a lovely film production about King Herod and his funeral procession.

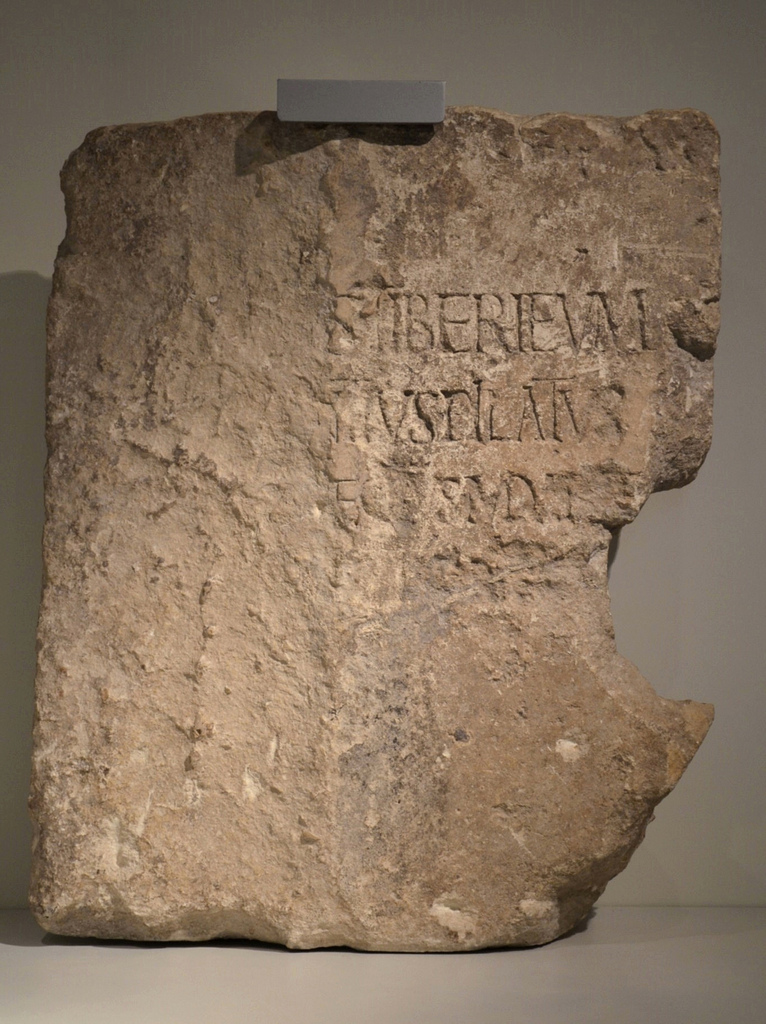

This post is dedicated to the memory of Prof. Ehud Netzer, who died in October 2010 following a fall while preparing an exhibition of the findings for the Israel Museum. The exhibition “The King’s final journey” finally opened in 2013, showing Herod’s impact on the architectural landscape of the Land of Israel. More than 200 objects found at Herodian sites, including Jerusalem, Jericho, Cypros and Herodium, were exhibited for the first time and the King’s reconstructed burial chamber.

PORtFOLIO

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Links:

-

- http://herodium.org/home/

- “The King’s final journey” – a virtual gallery tour of the 2013 exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem

Source:

- Herod the Great: The King’s Final Journey by Rozenberg, Silvia and Mevorah, David, The Israel Museum, 2013 (buy it here).