The Roman Temple Tawern (German: Römischer Tempelbezirk Tawern) is a reconstructed Gallo-Roman sanctuary on the Metzenberg in Tawern near Trier in western Germany. The original sanctuary was built in the 1st century AD above a major road leading from Divodurum Mediomatricorum (modern-day Metz) to Augusta Treverorum (modern-day Trier). It remained in use until the end of the 4th century AD.

Coordinates: 49° 39′ 51.31″ N, 6° 30′ 34.41″ E

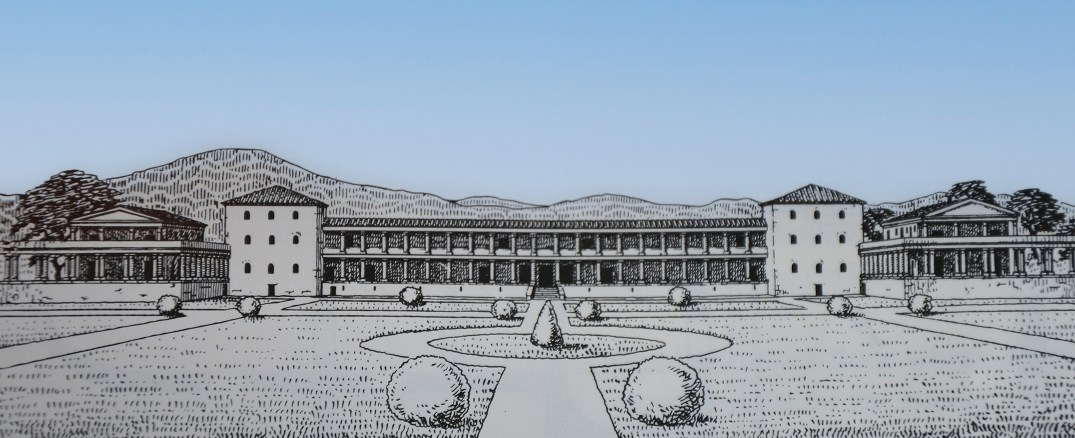

The sanctuary was excavated between 1986 and 1988, and seven buildings of various periods and differing sizes and plans were discovered within the complex. Under the direction of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum of Trier, the temple district and a large building were partially reconstructed on the original foundations. The finds (especially coins) revealed that the temple district was constructed in the first half of the 1st century AD and was used right up until late into the 4th century AD. Travellers on the nearby main Roman road would have stopped at the sanctuary to thank the gods for their successful journey or to invoke blessings as they made their way to Rome.

Mercury, the god of trade, commerce, and travel, was the main deity worshipped at the sanctuary. The slightly larger-than-life-size limestone head found in the water well came from a statue of the god. With the help of this find, a reconstruction of the statue was produced in 2002 and is now exhibited in the large Temple of Mercury. Five inscriptions found at the site were also dedicated to Mercury.

The sacred area, surrounded by walls, had a trapezoidal ground plan. It was entered through a small gate. The construction plan consisted of several phases. The first phase shows that five temples were arranged side by side. Various gods were worshipped, among them Mercury, the goddess Epona, Apollo, and Isis-Serapis. The temple district was later extended to cover an area of 48 m in width and 36 m in depth. Three temples were demolished to make way for the great main temple.

At the north-west corner of one temple, a water well originally more than 15m deep was unearthed. It was filled with stones, earth, and architectural parts. There were also fragments of inscriptions and figurative reliefs.

In the village of Tawern, at the foot of the Metzenberg, one can also see the remains of the small Gallo-Roman town (vicus) whose antique name was Tabernae. The name of the vicus was preserved in the modern name of the village, Tawern. The inhabitants of the vicus mainly provided goods and services for travellers. The nearby sanctuary attracted numerous pilgrims. A total of nine buildings were excavated on both sides of the Roman road.

PORTFOLIO

The Saarland and the Mosel Valley’s ancient Roman heritage has a lot to offer to tourists and scholars alike. More than 120 antique sights along the Moselle and Saar rivers, as well as in Saarland and Luxembourg, are a testament to the Gallo-Roman era north of the Alps (further information here).

The Saarland and the Mosel Valley’s ancient Roman heritage has a lot to offer to tourists and scholars alike. More than 120 antique sights along the Moselle and Saar rivers, as well as in Saarland and Luxembourg, are a testament to the Gallo-Roman era north of the Alps (further information here).

The temple area is not fenced, so it can be visited at any time. Admission is free.

Links: