The archaeological site of Tipasa is located on the Mediterranean coast of Algeria, approximately 70 kilometres west of the capital, Algiers. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that showcases an extraordinary mix of ancient cultures, including Punic, Roman, early Christian, and Byzantine influences. Tipasa was originally established as a Punic trading post and later grew into a prosperous Roman colony in the 2nd century AD, situated to the west of ancient Iol-Caesarea (modern-day Cherchell), the former capital of the Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis. Like other coastal cities in Algeria, Tipasa adopted Christianity in the first half of the 4th century AD. However, following the Arab invasion, the city gradually declined from the 6th century AD onward.

Coordinates: 36°35’35.1″N 2°26’47.0″E

Tipasa was a Punic trading post located along the sea route between Carthage and the Pillars of Hercules (Straits of Gibraltar). Very little remains of the early settlement, except for traces of a necropolis dating back to the 6th or 5th century BC. Rome conquered the city in the 1st century AD, and in AD 46, it was designated as a municipium with Latin rights under Emperor Claudius (Pliny NH 5.2.20). Later, it became a colonia under Emperor Hadrian, bearing the name Colonia Aelia Tipasensium (AE 1958, 129). In the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, Tipasa enjoyed a time of great prosperity. This period saw the construction of a 2.3 km long enclosing wall that featured 31 towers. Tipasa’s prosperity was primarily driven by trade in the Mediterranean, particularly in oil and garum.

During the reign of the Severan dynasty in the middle of the 3rd century AD, Moorish rebels were held at bay, allowing the cities of Africa to enjoy their greatest period of prosperity. Many of the public buildings that are still visible today were likely constructed during this time. With the ascendance of Christianity in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, the city’s physiognomy changed and reached a population of 20,000 inhabitants. The older buildings fell out of use or were demolished, and Christian basilicas were built. During the 5th century AD, the city faced challenges due to the Vandals’ annexation of Africa. However, it began to recover under Byzantine control one century later, leading to a modest renaissance characterised by repairs and expansions to several churches. At the end of the 7th century, the city was demolished by Umayyad forces and reduced to ruins.

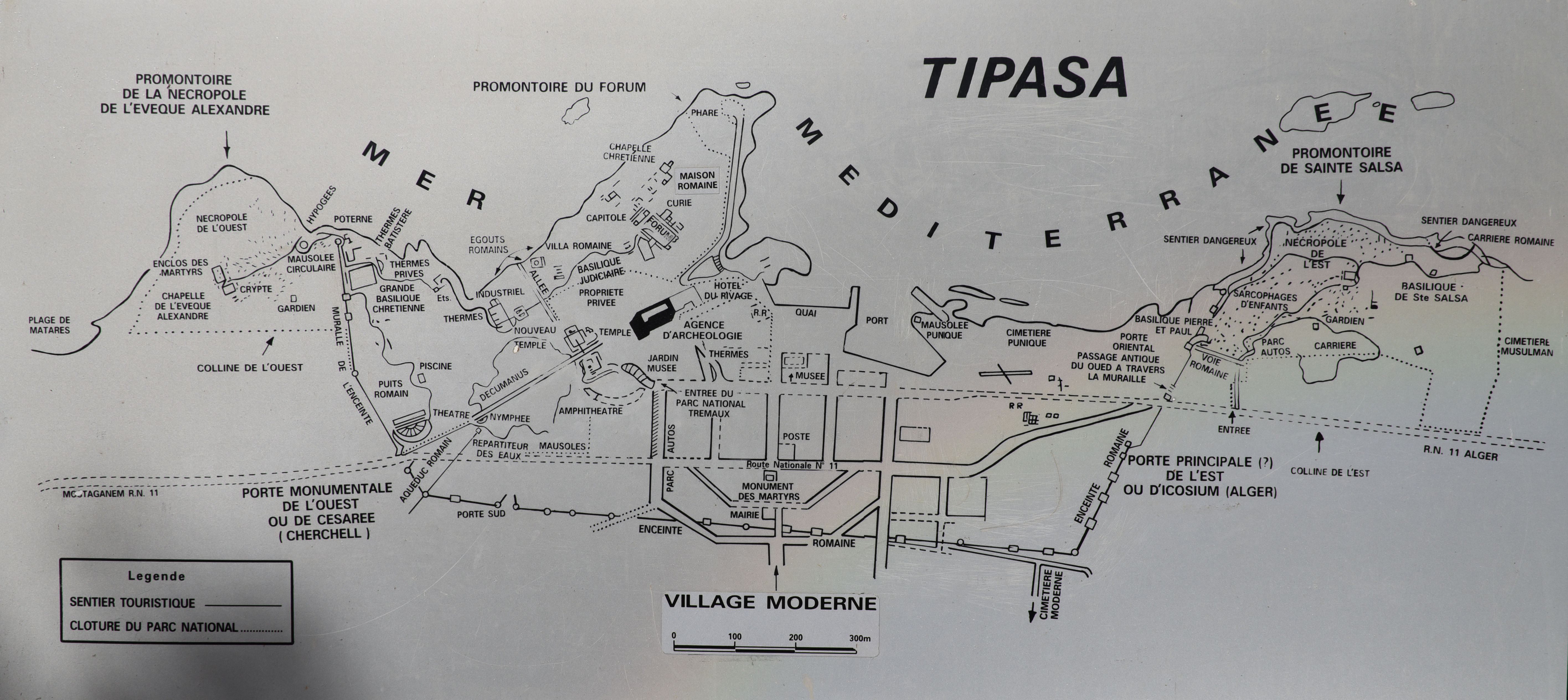

The main site of Tipasa is now a wooded archaeological park covering an area of 70 hectares. The entrance leads to an amphitheatre, and beyond it, a path guides visitors to the heart of the ancient town, where the two main streets, the paved cardo maximus and decumanus, intersect. To the east of the cardo lies the civic centre, including the Forum that originally featured porticoes on three sides, with the capitolium on the fourth side. This area also contains the curia (municipal assembly) and the civil basilica. Along the shoreline are several houses, including the so-called Villa of the Frescoes, a large residence measuring 1,000 square meters built in the mid-2nd century AD. The rooms of this villa open onto peristyles and are often decorated with mosaics and frescoes. Further inland is a theatre and a monumental semicircular fountain on the decumanus.

During Late Antiquity, Christians constructed various religious complexes, which included two basilicas, tombs, baths, and an impressive temple dedicated to the local martyr Saint Salsa. The Grand Basilica, featuring seven naves, was the largest Christian structure in North Africa upon its completion in the 4th century AD. The cemetery, adorned with carved tombs and inscriptions, provides valuable insight into the spread of Christianity throughout North Africa during this period.

The small museum outside the park showcases a variety of Punic and Christian funerary steles. It also features four tombstones dedicated to foreign cavalrymen who served in the auxiliary forces of the Roman army stationed at Tipasa. The museum also displays mosaics, including one depicting a captive family crouching with their hands bound.

PORTFOLIO

MUSEUM

Links & references:

- The Splendours of Roman Algeria

- Tipasa – UNESCO

- TIPASA Algeria – The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites

- Blas de Roblès, Jean-Marie; Sintes, Claude; Kenrick, Philip. Classical Antiquities of Algeria: A Selective Guide (p. 127). Society for Libyan Studies. pp. 120-163