Hegra, also known as Al-Hijr or Mada’in Salih, is one of the most significant archaeological sites in northwestern Saudi Arabia. It is located north of AlUla and the ancient capital of the Dadanite and Lihyanite Kingdoms at Dadan. Surrounded by vast desert plains and impressive sandstone cliffs, Hegra is famous for its monumental Nabataean tombs, which are intricately carved into the rock. Once a thriving city during the Nabataean Kingdom, Hegra was the second most important city after Petra. The Nabataeans, originally a nomadic Arab tribe, flourished between the 4th century BC and the 2nd century AD by controlling trade routes that connected southern Arabia to the Mediterranean.

Coordinates: 26° 47′ 30″ N , 37° 57′ 10″ E

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Hegra region was inhabited long before the Nabataean period. Bronze Age funerary structures and early inscriptions suggest human activity in the area as early as the 3rd to 2nd millennium BC. The earliest known inhabitants of Hegra were the Lihyanites, who established the site as a trading station along important north-south caravan routes. The arrival of the Nabataeans in the 1st century BC marked a significant transformation for Hegra, turning it into a prosperous urban centre. As skilled traders and expert hydraulic engineers, the Nabataeans developed advanced water management systems, establishing Hegra as a key hub along caravan routes connecting Arabia with the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia. During this period, particularly under the rule of Aretas IV (9 BC – AD 40), the city flourished, covering an area of 1,500 hectares. It featured a sophisticated network of wells that supported agriculture in the desert, and its inhabitants created impressive rock-cut tomb façades.

Carved from towering, honey-coloured rocks that rise from sunbaked sands, the tombs form a necropolis surrounding Hegra’s city centre. Little of the mud-brick architecture of the walled city remains, but the tombs have remarkably withstood centuries of harsh sunlight and erosion. More than 130 surviving wells, originally established by the Nabataeans, demonstrate their expertise in water management. Most of the tombs feature intricately decorated façades, providing insight into the relationships that this Arab tribal society had with other cultures, until it lost its independence to Rome in AD 106.

All the tombs (111 in total, 94 of which are decorated) date back from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD, and many display carvings of eagles, mythological figures, snakes, and sphinxes. More than 30 of Hegra’s tomb façades bear inscriptions etched in the rock. They are legal texts that list the owners’ names and, sometimes, their roles in the community. They are written in the Nabataean script, a variety of Aramaic that later developed into Arabic. Some tombs serve as final resting places for high-ranking officers and their families, whose inscriptions indicate that they carried Roman military titles such as prefect and centurion into the afterlife. In addition to the tombs, chambers, shrines, niches, and other unique structures have survived.

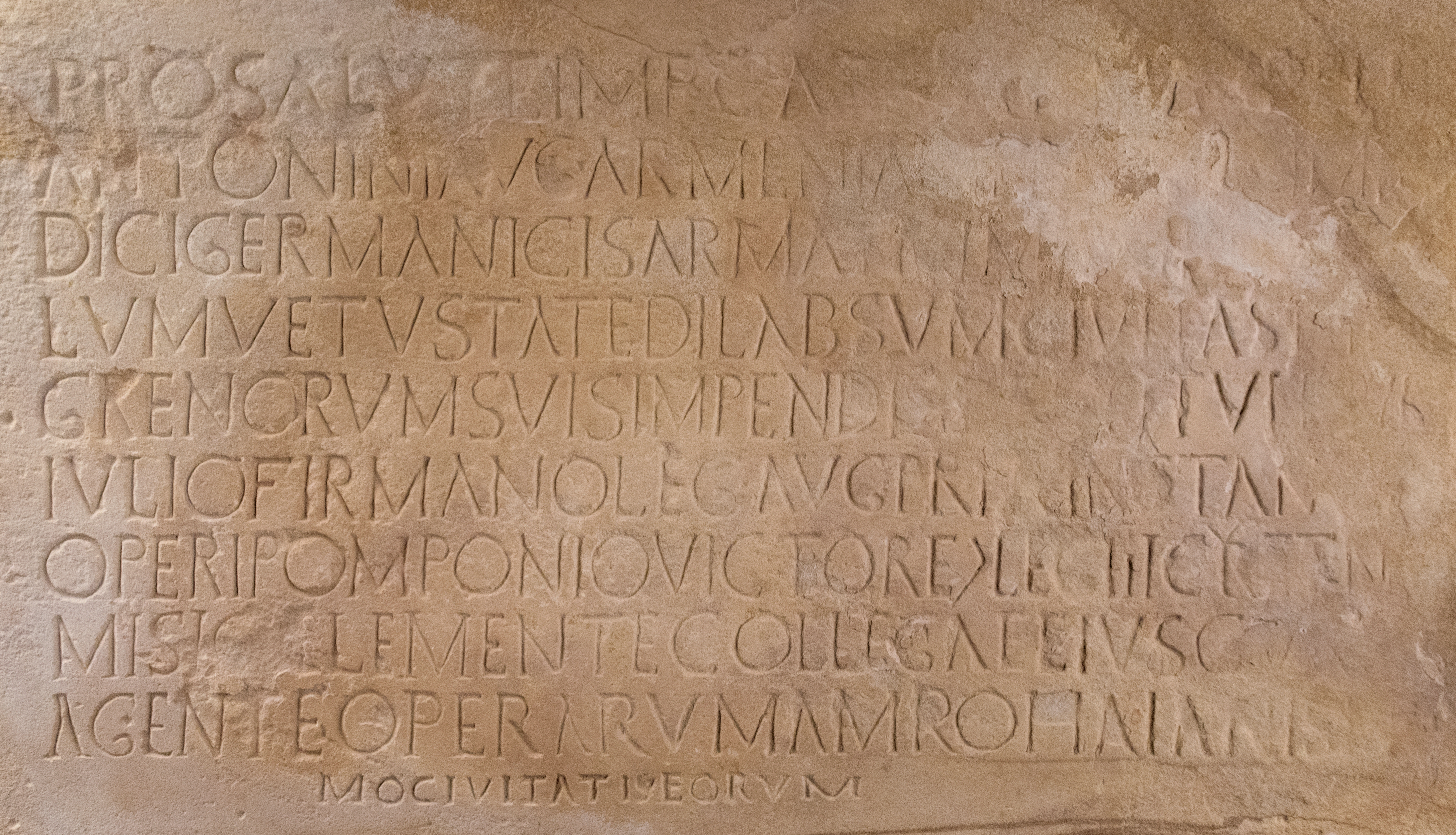

In AD 106, the Roman Empire annexed the Nabataean Kingdom, incorporating the city of Hegra into the province of Arabia Petraea. Evidence of Roman military presence in Hegra is found in the epigraphic record. A Greek inscription refers to a painter associated with the Legio III Cyrenaica, while Greek graffiti created by soldiers from the Ala Getulorum and Ala Dromedariorum can be seen on the rocks along the ancient north-south trade route that passes by Hegra. Additionally, a monumental Latin inscription, discovered in 2003 and dated to AD 175–177, mentions the restoration of a monument, likely the city wall, with the assistance of two centurions from the Legio III Cyrenaica (source).

The city was not truly Romanised, however, and no forums, theatres or paved roads have been identified there. The city was primarily a military outpost. With its ramparts and many wells, it was an ideal base for the garrison guarding the border and the inland route between Syria and southern Arabia. The archaeological excavations of the last ten years have uncovered a Roman camp with baths, built in the 2nd century AD and abandoned in the 4th century AD, and a gate from the Nabataean rampart, reconstructed by the Roman army between AD 170 and 220.

By the early Islamic period, Hegra had largely been abandoned, leaving its grand façades and silent streets to the desert landscape. European explorers in the 19th century renewed scholarly interest in Hegra, and systematic archaeological research throughout the 20th and 21st centuries has greatly expanded understanding of the site. In 2008, Hegra was designated Saudi Arabia’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site, and ongoing conservation efforts continue to shed new light on this extraordinary crossroads of ancient civilisations.

The main archaeological sites in Hegra include:

- The settlement area dedicated to daily life, conveniently located in the centre of Hegra, a 50-hectare site surrounded by a defensive wall and dotted with residential buildings (not accessible to the general public)

- Jabal Ithlib and Ith 78, the worship area, located to the east of Hegra

- The burial area where the iconic monumental tombs were carved into many large rocks (Jabal Banat, Jabal al-Mahjar, Al-Khuraymat, Al-Jadidah, Jabal al-Ahmar). There’s an interactive tomb map online that lets you zoom into each necropolis and click individual tombs (link). Not all necropoises are accessible to the general public.

- The agricultural oasis, which included 130 wells, scattered in the western, northwestern and northern parts of Hegra (not accessible to the general public)

The tombs of Hegra are distinguished by the variety of their decorations and architectural structures, reflecting the social prestige of Nabataean families. Among the main types identified are:

- Proto-Hegra Type 1 (approx. 24 tombs): Features pilasters, an Egyptian-style cornice (entablature), and two symmetrical half-crowsteps crowning the facade.

- Proto-Hegra Type 2 (approx. 12 tombs): Similar to Type 1 but includes an entablature enriched by a frieze.

- Hegra Type Tombs (approx. 15 tombs): Characterised by two entablatures separated by an attic.

- Crowstep Tombs (One/Two Rows): Tombs featuring one row (12) or two rows (14) of stepped merlons at the top.

- Half-Crowstep Tombs (8 tombs): A cornice formed by two half-crowsteps on an Egyptian-style entablature.

- Arched Tombs: A unique, rare type using an arch as a crowning element.

Simple Facades: Undecorated or incomplete tombs.

Funeral practices in Hegra followed a carefully structured Nabataean ritual that began at the home of the deceased and ended in a rock-cut tomb. After death, a necklace of fresh dates was placed around the neck, and the body, naked or nearly naked, was wrapped in several successive shrouds. First, it was enveloped in a red-dyed wool shroud, then in an undyed linen shroud coated with a mixture of vegetable oils and resins, and finally in a coarser linen shroud that absorbed additional resins. These layers were secured with textile ties and enclosed in a leather shroud made from stitched pieces, with a funerary mask placed over the face. The prepared body was then carried, likely in procession with family members, to the tomb, where it was laid in the burial chamber. After the ceremony, the tomb was sealed with a wooden door or stacked stone blocks, marking the conclusion of the funerary rite.

Archaeologists investigating the tombs carved into the Jabal Ahmar necropolis unearthed a nearly complete skeleton of a Nabataean woman in tomb IGN 117. The tomb, containing the remains of as many as 80 individuals, bore an inscription, dated to AD 60/61, identifying it as belonging to “Hinat, daughter of Wahbu,” who had built it for herself and her descendants. Analysis of her bones showed she was a woman of about 40–50 years of age and roughly 1.6 meters tall, and her burial suggested she was of medium social status. Using the well-preserved skull and modern forensic and 3D reconstruction techniques, scientists have been able to create a facial approximation of Hinat, offering a rare and tangible glimpse of an individual from Nabataean society two millennia ago.

PORTFOLIO

Qasr al Farid

Qasr al Farid, also known as The Tomb of Lihyan Son of Kuza, is a 1st-century AD tomb carved into a single huge rock. It is the most famous and the largest tomb in Hegra. The tomb is an iconic example of Nabataean funerary architecture and stands isolated. It is carved into a massif about 23 metres high and 18 metres wide, with the access platform raised approximately 4 metres above ground level.

The Jabal Banat necropolis

The Jabal Banat necropolis is one of the most striking burial clusters at Hegra. It consists of 31 Nabatean tombs dating from AD 1 to 58 (Tomb IGN17 to Tomb IGN45). The tombs include fine inscriptions about the eminent figures for whom they were intended and decorations such as birds, monsters, and human faces. The largest among them is IGN 20 (16m high).

The Jabal al-Ahmar necropolis

The Jabal al-Ahmar Necropolis consists of twenty-two tombs, numbered from IGN111 to IGN130.1, spread across two sectors and divided into three rocky outcrops, some of which have recently been uncovered. The remains of a 2,000-year-old Nabatean woman named Hinat were excavated from one of these tombs (read more here).

Jabal Ithlib

Jabal Ithlib, located northeast of Hegra, features a complex of rock-cut structures that includes two triclinia, twenty-one sanctuaries, niches, and basins. This complex is not a necropolis; rather, it serves as a caravanserai and an entry point for caravans travelling to the necropolises and residential areas. The Ith20 triclinium (also known as IGN16 or Diwan) is situated at the entrance of the canyon in the western sector of the Ithlib massif, while the second, smaller triclinium is located further south within the massif.

Links: