Located in the village of Nennig in the delightful Upper Moselle Valley, the Roman Villa Nennig (German: Römische Villa Nennig) houses a richly illustrated gladiatorial mosaic, one of the most important Roman artefacts north of the Alps. Protected by a dedicated building built about 150 years ago and covering an area of roughly 160m2, the mosaic vividly portrays musicians, hunting scenes and gladiatorial contests.

Coordinates: 49° 31′ 44.56″ N 6° 23′ 5.03″ E

In the 3rd century AD, the mosaic paved the atrium (reception hall) of a large villa urbana which a wealthy Roman had built on the road between Divodurum (Metz) and Augusta Treverorum (Trier). The mosaic later disappeared below ground until it was discovered by chance by a farmer in 1852. The excavations conducted between 1866 and 1876 revealed only a part of the once splendid and extensive ground, the foundation walls of the imposing central building, and several adjacent buildings. A coin of Commodus (struck ca. 192) found under the mosaic during the restorations of 1960 dates the villa’s construction to the end of the 2nd century or the beginning of the 3rd century AD.

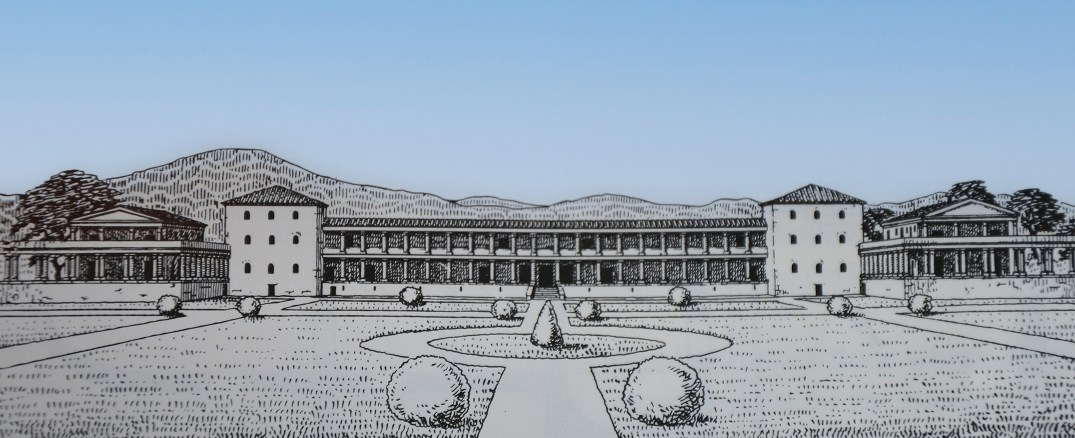

The villa complex included a bath house with heated rooms, small pavilions and magnificent gardens. A two-storied colonnaded portico (140 m long) flanked by three-storied tower wings with massive walls ran across the façade of the main building. Beyond these, at either side, two temple-pedimented structures flanked the villa.

The mosaic comprises seven octagonal medallions surrounding two central quadrangles, one decorated with a scene of gladiatorial combat, the other occupied by a marble basin. An elaborate pattern of geometrical designs borders each scene. Walking around the interior of the protective building, the entire scene of the mosaic can be viewed from a raised platform.

PORTFOLIO

The beginning and the end of the Roman games were often accompanied by music. The mosaicist has depicted the water organ (hydraulis), known in the ancient world since 300 BC. The 27 organ pipes rest on a hexagonal podium that also stores water for the organ. The organist plays the keyboard situated behind the pipes. The curved horn, which is braced and supported on the shoulder of the player by a crossbar, is a cornu.

The games usually began with venationes (beast hunts) and bestiarii (beast fighting) gladiators. Here the beast is wounded by the venator’s spear and tries to pull the javelin out. It only succeeds in breaking it in half. Delighted with his success, the proud venator received the crowd’s acclamation.

Another variety of venatio consisted of putting animals against animals. In this scene, a wild ass, laid low by blows from the tiger’s paw, has fallen to the ground. Standing proudly, the victor of this unmatched contest looks around before starting his bloody feast.

This was the first of the illustrated panels to be discovered in 1852.

A bear has thrown one of his tormentors to the ground while the other two attempt to drive the animal off. The venatores are wearing knee-breeches and very broad belts in addition to the leg wrappings. Later their clothing was reduced to the tunica.

The introduction to the gladiatorial contests consisted of a prolusio (prelude). The various pairs of gladiators fought with blunted weapons, giving the foretaste of their skills.

In the afternoon came the high point of the games; individual gladiatorial combats. These were usually matches between gladiators with different types of armour and fighting styles, supervised by a referee (summa rudis). This scene simultaneously represents the highlight and the conclusion of the games.

The Saarland and Moselle Valley’s ancient Roman heritage has much to offer tourists and scholars. More than 120 antique sights along the Moselle and the Saar rivers, the Saarland and Luxembourg are testaments to the Gallo-Roman era north of the Alps (further information here).

The Saarland and Moselle Valley’s ancient Roman heritage has much to offer tourists and scholars. More than 120 antique sights along the Moselle and the Saar rivers, the Saarland and Luxembourg are testaments to the Gallo-Roman era north of the Alps (further information here).

Opening hours:

April – September: Tuesday to Sunday 8:30 am – 12 noon and 1 – 6 pm

October, November and March: Tuesday to Sunday 9 – 11:30 am and 1 – 4:30 pm

Closed from December to February and on Mondays

Website: http://nennig.de/sehenw/nennig.html

Sources:

- The Roman Mosaic at Nennig: A Brief Guide (n.d.) by Reinhard Schindler

- Eckart Köhne, Cornelia Ewigleben, Ralph Jackson, Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000

I have never seen such stunning mosaics Carole Your photographs are magnificent. Thanks for sharing..

LikeLike

Amazing! Thank you for sharing your travels!

LikeLike

As with others I imagine, I have seen various representations of this mosaic. But in your presentation the photographic details, accompanied with explicative text, bring a richness & vitality to the matter never quite experienced before. Please do accept my sincerest gratitude

LikeLike

Pingback: Annum novum faustum felicem vobis! | FOLLOWING HADRIAN